by Heather Larkin

Note: Please only respond to this thread if you have read the full JITP article linked above.

Introduction

Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have been involved in an ongoing collaboration with Kaiser Permanente’s Department of Preventive Medicine, where they have designed a large and epidemiologically sound study exploring the role of “adverse childhood experiences” (ACEs) on social and health outcomes later in life. This research brings a distinct and compelling relationship between ACEs, health risk behaviors, and physical and mental health into awareness. This article outlines these research findings, pointing also to the role of ACEs in homelessness and criminal justice involvement and addressing service delivery implications. Integral Theory is used to explain ACEs as an underlying syndrome, and Integral Restorative Processes is presented as a useful and flexible intervention model to guide a comprehensive and effective response.

Introduction

Recent research by Kaiser Permanente and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) strongly implicates childhood traumas, or “adverse childhood experiences” (ACEs), in the ten leading causes of death in the United States. ACEs include physical violence and neglect, sexual abuse, and emotional and psychological trauma. ACEs are associated with a staggering number of adult health risk behaviors, psychosocial and substance abuse problems, and diseases. History may well show that the discovery of the impact of ACEs on noninfectious causes of death was as powerful and revolutionary an insight as Louis Pasteur’s once controversial theory that germs cause infectious disease. His ideas were slow to be adopted but are now universally accepted. Similarly, ACEs parallel what Pasteur offered—an underlying syndrome implicated in noninfectious causes of death. This is truly a remarkable discovery that is likely to change the way in which the field of medicine is viewed and practiced. The impact of ACEs is felt not only in health care but also in businesses because of employee absenteeism, in homelessness, and in the criminal justice system. ACEs likely cost untold millions of dollars a year.

Anda, one of the primary ACE researchers from the CDC, described how shocked and saddened he was to discover that ACEs are so distressingly common. The frequent strong and graded relationships between ACEs and a variety of medical conditions were also clear in the findings. The authors of the ACE study and other researchers provide a useful framework for conceptualizing the life course pathway of ACEs and suggest implications for public health responses. Their contribution is critical in terms of clarifying diagnosis. In their effort to both theoretically explain their work and offer a treatment model for a comprehensive response, the ACE study authors would benefit in learning of Integral Theory and the Integral Restorative Processes (IRP) model. Current treatment for leading causes of death generally is not informed by knowledge of the impact of ACEs and thus addresses aspects of ACE consequences in a piecemeal fashion. As a result, the underlying syndrome is not often taken into consideration.

This article will begin with a brief overview of Integral Theory, which is presented as uniquely capable of explaining the ACE results. Next, the ACE literature is reviewed, outlining its findings in regard to health risk behaviors, mental health and substance abuse problems, and medical problems. The role of ACEs in homelessness and the criminal justice system is also addressed, along with a discussion of the importance of a comprehensive and coordinated service response to ACEs. An Integral explanation of ACEs is then provided. Becker’s Nobel-prize winning work offers a social economic perspective in understanding the interplay between personal choices and social interactions. Numerous studies demonstrate that early childhood interventions provide high rates of return in human capital. This also makes a powerful argument for comprehensively addressing ACEs. Finally, IRP is a model, derived from Integral Theory, which can appropriately respond to ACEs in a comprehensive and coordinated fashion that draws on what we know about how to support people in body, mind, and spirit within self, culture, and nature.

Integral Theory Overview

Integral Theory brings together the work of various developmental theorists, along with other research, such as Daniel Goleman’s work on emotional intelligence and Howard Gardner’s recognition of multiple intelligences.5 These developmental lines move through stages of increasing structural complexity, and those stages cannot be skipped. Each new stage transcends and includes its predecessors. Each line of development involves an individual’s increasing functional capacities in particular areas and contributes to a person’s general altitude or overall stage of development. This development is all happening in the context of self, culture, and nature. In other words, development does not occur in a vacuum but involves interaction between the person and the collective environment—social, cultural, and ecological.

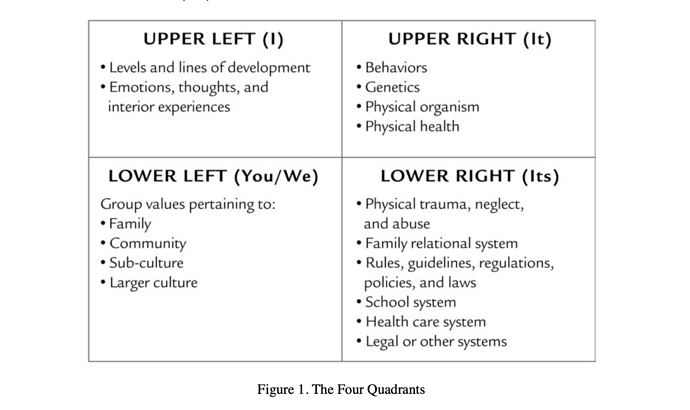

These mutual interactions are represented by the four quadrants, which are actually dimensions that an individual possesses, as well as perspectives from which development and events can be viewed. The “I” dimension-perspective or Upper-Left quadrant (UL) focuses on the interior of the individual self and developmental processes that the individual undergoes. The “I” is subjective, so understanding the “I” involves asking questions because it cannot be “seen.” The “We” dimension-perspective or Lower-Left quadrant (LL) represents shared values and worldviews that play a role in cultural interactions, such as agreements about how “We” treat each other. The “We” is intersubjective—a culture is made up of mutual understanding (I + YOU = WE). The exterior of the individual includes the brain, the physical organism, and behaviors, all of which are represented by the “It” dimension-perspective or Upper-Right quadrant (UR). The social system and environment constitute the “Its” or Lower-Right quadrant (LR). The UR and LR quadrants are otherwise known as “nature” (including human productions that can be seen with the senses). These refer to objective and interobjective phenomena, respectively, or things that can be observed from a third-person perspective. As we can see in figure 1, the upper two quadrants are oriented to the individual, and the lower two quadrants are oriented to the collective. The Left-Hand quadrants are subjective/intersubjective and the Right-Hand quadrants are objective/interobjective. These four quadrants mutually interact with one another and evolve together, making overall development a four-quadrant affair.6 Identifying these aspects of development becomes extremely useful in both understanding the ACE findings and fashioning a comprehensive response.

ACEs can have their origin in almost any quadrant, but they typically occur where human beings interact—they tend to be acts of violence institutionalized in the family system (LR) on a consistent basis. In addition to setting off repercussions in the other quadrants, the same LR actions (such as being part of a family system that involves physical abuse or witnessing trauma) may affect people differently, depending upon what is going on in the other quadrants. Family meanings and cultural values (LL) related to these actions can actually be quite diverse. Individuals also have unique psychological strengths (UL) and behavioral coping strategies (UR) available to them. The extent to which ACE interventions occur in service systems (LR) may also vary among communities. These services, or lack of services, are both shaped by and influence cultural values (LL).