Watch as Ryan and I discuss the importance of cultivating and inhabiting a “confident humility” with relation to our own physical bodies, mental processes, and spiritual health. We also have a fun segment at the end designed to put your own humility to the test, by looking at 10 common integral caricatures — stereotypes that many of us fall into at one point or another during our Integral lives.

There is a phenomenon that has become fairly well known in recent years known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. If you are not familiar with that term, it describes the fact that, on average, people tend to greatly overestimate their own capacities and competences. In other words, the majority of us are completely out of our depths when it comes to some important aspect of our lives — our work, our skills, our overall sense-making and maps of reality, etc. — and we surround ourselves with any number of cognitive biases that prevent us from seeing just how limited our views and our self-concepts truly are. In other words, “the first rule of the Dunning-Kruger club is you don’t know you’re in the Dunning-Kruger club.”

It’s one of the well-known traps of Integral — because it is so comprehensive and includes so much of our inner and outer worlds, it can tempt us into thinking we know… well, everything.

What’s worse, if we don’t keep a careful eye on our ego, it doesn’t take too long before we’ve wrapped an entire identity around our epistemic over-certainty, which only leads to further social fragmentation, tribalism, and culture wars — even within the integral space itself.

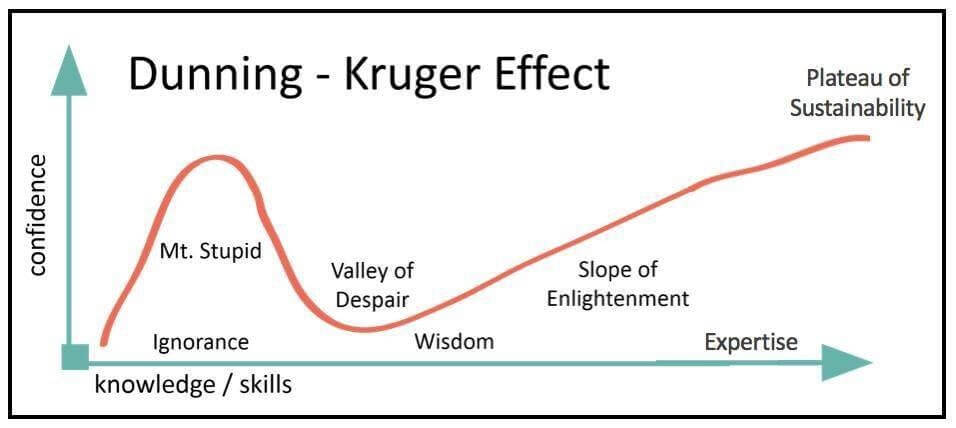

Here is a popular illustration of the Dunning-Kruger effect:

As you look at this graphic, take a moment to reflect: where do you think you are on this scale in various facets and dimensions of your life? Can you recognize those areas where you may still be standing on “Mount Stupid”, or the “Valley of Despair”, or even the “Slope of Enlightenment”?

Because make no mistake, this phenomenon is not describing “dumb people” or people who are “less developed” than yourself. It also describes doctors, PhDs, philosophers, artists, and many of the greatest minds of our time, regardless of where they are in their own growth and development. The sorts of cognitive biases that produce the Dunning-Kruger effect are legion, and made all the more ubiquitous by social media and all the various selection pressures that come with it.

So if you are able to take a moment to pause and reflect on where you might be on the Dunning-Kruger path — congratulations! You are practicing healthy epistemic humility right now at this very moment.

So how do we prevent ourselves from falling into the trap of over-certainty? By committing to the ongoing work of growing up, cleaning up, and waking up within our own interiors, and then bringing more flexibility, curiosity, and multi-perspectival awareness to our epistemic maps of reality. In other words: cultivating our interior confidence, and then aligning that with humility when it comes to how we navigate the world around us.

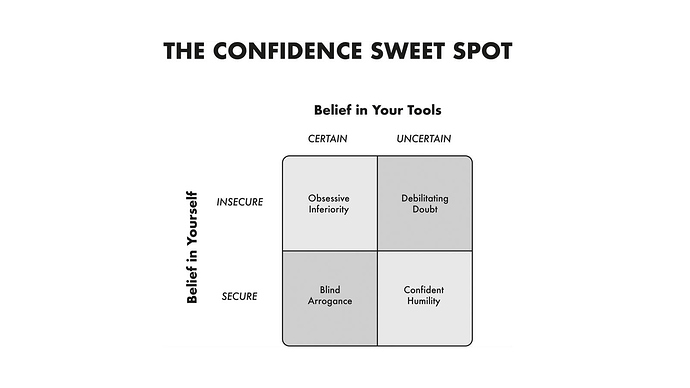

In his bestselling book Think Again, author Adam Grant uses the following graphic to illustrate the “sweet spot” of confident humility:

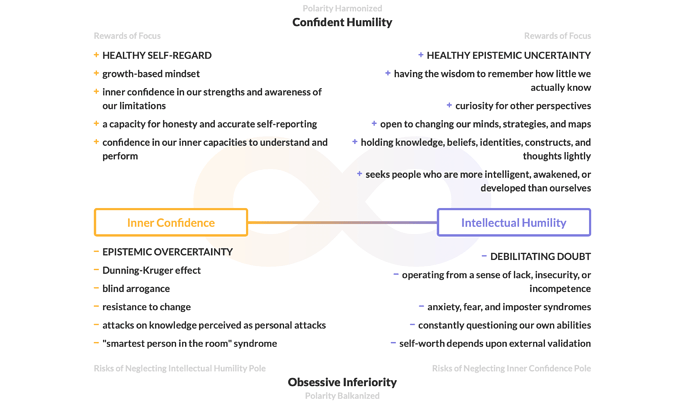

In this episode we offer another way to consider the relationship between confidence and humility, by enacting it as a polarity that needs to be constantly managed, integrated, and re-integrated:

By holding “confident humility” as a polarity rather than some final state we hope to arrive at, we can better identify and navigate the various qualities that arise as these two poles are either harmonized or balkanized. After all — we might think we’ve arrived at something like “confident humility” in our own lives, but how do we know that is not just yet another Dunning-Kruger distortion?

Finally, Ryan and I have a little bit of fun at the episode, taking a look at 10 common traps that Integral enthusiasts often seem to fall into. As with everything else, this segment should be taken lightly, and in the spirit of playful self-reflection. How many of these people have you been over the years?