[blockquote cite=“Wayne Shorter”]“I believe that life is the ultimate adventure. The single moment is the DNA of eternity.”[/blockquote]

Wayne Shorter, likely the greatest jazz composer since Thelonious Monk, was also one of the most influential tenor and soprano saxophonists in the post-John Coltrane period from the mid-1960s onward. His death on March 2, 2023, at the age of 89, marks the end of a musical life that spanned a panoply of styles and configurations, from hard bop to electronic fusion and funk to Brazilian and Caribbean to orchestral and the avant-garde, all suffused his own idiosyncratic melding of sounds and sensibilities which seemed to reach from the heat-center of the earth to the infinite expanses of the cosmos.

As Duke Ellington would say of the great artists of his day, Wayne Shorter is “beyond category.”

As a jazz writer since the mid-1990s, I have been fortunate to meet and interview legends whose legacies in American improvisational music will be spoken of with the same reverence as the greatest musicians in the European concert tradition. Wayne Shorter, without a doubt, is in the upper reaches of such jazz grandmasters, not only for his unique instrumental style and compositions but for his perspectival brilliance. That’s why I was honored to share with Integral Life a conversation with Mr. Shorter over a decade ago.

Just as his music will live on in recordings and memories as fine art, may his words continue to illuminate metaphysical and aesthetic depths that reverberate far beyond the prosaic into the realm of profound truth, goodness, and beauty.

—Greg Thomas

Among the many benefits and blessings of being a jazz journalist, and having a weekly column in the one of the nation’s largest circulation dailies—the New York Daily News—is the honor of speaking with legends of the music, artists whose mark on the jazz idiom will remain long after their physical lives come to a close. Quite a few of these artists aren’t only geniuses of music. The philosophical and spiritual insights of guitarist Pat Martino, for instance, were featured on this very site last year. The profound point of view of tenor sax icon Sonny Rollins was featured in fall 2010.

Now another master beckons: Wayne Shorter. In April 2012 I interviewed Mr. Shorter for a feature story for publication in the Daily News. He was to about to perform at Jazz at Lincoln Center with his quartet, and soon thereafter at the United Nations for the first International Jazz Day, launched by his friend, musical mate, and fellow Buddhist Herbie Hancock. As usual in instances like this, where a master musician’s life and career, past and current, has to be whittled down to less than 1,000 words for a print newspaper piece, there was great material that ended up on the cutting room floor.

Since Shorter is perhaps the greatest composer in jazz, whose legendary tenures with Art Blakey, Miles Davis, and Weather Report make him beloved by music lovers the world over, it would be shameful not to pick up the pieces, so to speak, and put them together for readers of Integral Life.

To describe the experience of speaking to Shorter, I’ve written elsewhere that he “can take you around the world in 80 minutes of conversation. High-wire discussions spiral through music, comic books, science, film and philosophy in a seeming blink.

“Similar to his saxophone playing, Shorter is highly associative, with one phrase or idea leading to another, sometimes directly, at others in sideways patterns or leaps of discursive thought or sounds.”

Among the many things I found fascinating about speaking with Mr. Shorter, a few stand out. He’s very digressive, but if you listen and read closely, and follow his examples, there are threads that tie his points together, however oblique they may seem upon first hearing or reading them. But his technique of conversational engagement is similar to trading fours or eights in jazz. The questions provoke improvisational answers, which lead to more questions, and so on, but his multi-level mastery allows him to fill gaps in your own understanding or point you in directions you likely haven’t considered.

So if you’re basic, prosaic, he might riff abstractions that make your head spin. Yet if you come from a place of abstraction, intellectual, philosophical or spiritual, he can bring you down to earth by mentioning his times with the legends of jazz or your grandma’s folk wisdom.

You’ll see that the meaning and substance of his mission often touch upon Integral themes. Check out some of his compositions and playing in the You Tube clips below. First, however, I invite you to feast on the mind and perspectives of Wayne Shorter, in his own words . . .

Greg Thomas: Music and the other arts tap into creativity, which in my estimation is a spark of wisdom and impulse to infinity. You’ve often said that you don’t believe in beginnings or endings. Why?

Wayne Shorter: I do more than believe that there’s no such thing as a beginning or end. Those words, to me, are artificial and temporary word tools to get us from one place to another. But the ultimate of it all is . . . I’ve been reading Dr. Stephen Hawking’s new book [The Grand Design, Bantam Books]. . . It’s very, very interesting when he stated that the universe created itself.

(After the interview I looked up the book, and came across this: “Spontaneous creation is the reason there is something rather than nothing, why the universe exists, why we exist.”)

That’s why I think creating something is a challenge. Jazz is something that’s done in the moment. How do you rehearse being in the moment? Being in the moment is one of the processes that free us from being fearful of the unknown. A lot of people are afraid of the unknown, which is why we have “conservatives” and “liberals.”

The conservative stuff attaches itself to business, commercial gains, ’cause you have to have a status quo, a formula to live within. “Do not disturb” is on the door. No changes.

I like that line in the first Jurassic Park movie, where the Jeff Goldblum character says: “Life finds a way.”

From dating to business, a lot of people are speaking from planning and strategy, but now’s the time to speak to each other as we play music—by being in the moment. If you’re in the moment, that’s when you’re going to undress yourself. You’ll take off all of the b.s. layers that we’ve been conditioned to. And get free from being hijacked from the cradle.

Parents do the best that they can. I’m not saying that parents are hijackers, because they’ve been hijacked [too.] But without being hijacked, how do you know you’ve been hijacked? You know what I mean, salt and pepper?

GT: Yes. Relativity.

WS: It’s kind of like The China Syndrome, where people are in hellish situations and fall in love with it and become comfortable in hell, comfortable in a divorce situation, comfortable with hating somebody, because of these kinds of jive emotions.

GT: Being conditioned and getting used to it habitually.

WS: Emotions are hijacked too. That’s [really] the way I feel.

GT: You related being in the moment to jazz. And on another level, being in the moment is now, not the past or the future. Now is the only reality on this plane of existence.

WS: In the philosophy I’ve been involved with, the moment, now, is the only place that you can change and alter the past and determine the future. In other words don’t let the past influence you. Alter, to me, means don’t keep living by it. Start being the director, actor, producer of the movie of your own life. This is a challenge. I believe that life is the ultimate adventure. The single moment is the DNA of eternity. Nothing will be destroyed.

GT: We learned in science classes that matter can neither be created nor destroyed.

WS: When you write music with the intention of a hit, you cater to what you think people are used to. [Next Shorter riffs on how in Hollywood acting today, the young actors, male or female, speak in the same tessitura, the same range, with Tom Cruise a model example for male actors. He says there aren’t people with cracks in their voices, and rattles, or real deep voices like Walter Marshall, the actor who played in the Blaxploitation flick in the early ‘70s, Blacula.]

I’m talking about that formula that they want in movies, the vocal sound. It’s in singing too. [Like] singers who do all these embellishments without studying harmony. They think it will take too long, and interfere with them making money and their “natural gift.” Nooo.

GT: As master drummer Michael Carvin says, you’ve got to learn those rudiments. Many say that you’re the living master of jazz composition. Since it’s obviously not about making hits, what is your intentionality and process?

[Before responding to my question directly, or rather, indirectly, he continues his previous train of thought.]

WS: You know what drives that? It’s the way the world actually is. It’s high resolution. The really easy access, accessible stuff has closed everything: music, movies, books. This gets high visibility and representation, 24 hours a day. We’ve had 100 years of radio, now TV, except now we have the Internet and computers. The attempt to control the Internet is frustrating many of the commercial minded business people who never really took a chance by climbing over the fence and becoming an artist, and not worrying about making some money.

They have a limited view; they don’t know what a mission is.

So my mission is to keep myself consistently unsedated and dispelling the venom in myself, as much as I can, as long as I live and eternally. It’s an eternal quest for me because, as I said, there ain’t no such thing as the end. If there is, that’s very suspect. It’s a trap. Then I become what I’ve been fighting.

GT: To put it in my own words: it’s an expression of being alive, conscious, and striving to be as awake and aware as possible as opposed to being sedated, dis-eased, by what we were born with as we came into human form.

WS: What we’ve been invaded with from the cradle. Allow your real person to emerge.

Because when you look at it, and you ask someone what’s your real name? They say their given name. No. They might say “homo sapien.” No.

Your real name is something that’s done that hasn’t been done, that’s hard to do but must be done, which validates the ultimate adventure.

GT: What’s the ultimate adventure?

WS: The ultimate adventure is when each entity can penetrate one another where they recognize their actual mission that’s been covered up, of having wisdom take over instead of just knowledge. It’s not enough to just say I’m honest and truthful, but truth doesn’t mean that much unless you make some value out of the truth.

To be fearless, brave, courageous, with the time that it needs to come about, and to learn what wisdom is, and learn what the person’s real, eternal identity is. And that eternal identity is evolving all the time.

We have a phrase, “When we start to do human revolution within ourselves, that’s when great, great change takes place.” [That’s] the opposite of forced enslavement and conditioning.

GT: You become free from the inside going outward.

WS: Right. You get the whole cognitive mechanism of learning, and to be able to recognize, by yourself, the decisions and directions you go in, moment to moment, in the moment.

GT: That’s what I learned years ago about wisdom. That wisdom is making the right decisions and being all that you can be, in every single moment, as you course through this world.

WS: And not to be forced, or hard-nosed about it. Sometimes you gotta just relaaxx, man, and stop worrying about stuff based on how you perceive.

GT: Let it flow. But to get beyond the conditioning, and the viruses, takes a process, a part of which is meditation, to come into the realization of the true you, right?

WS: Yea, all that. It’s just simple things sometimes that a grandmother might say. Like “Stop making a mountain out of a molehill.” They were not totally hijacked, our grandparents. So if we have the wisdom to really listen to the stuff that they really meant.

Sometimes I would say a little something like this when speaking with Miles [Davis]. And Miles would be in that same zone. We’d just talk about this just a little bit, some kind of philosophical something, and he’d say, “Why don’t you play that?” I said whoa. In a sense, Miles was about that.

I discovered some things about [drummer and band leader] Art Blakey. He was a person I thought I knew when I was with him, but there’s a whole lot that I didn’t know. He had a lot to do with turning the road for young children in Japan. Sometimes when we’d play there, we’d go home and he’d stay. I later found out he was giving drum classes with young kids, in 1960, ’62, ’63. I heard recently that those students are adults now and thank Art Blakey for them being strong adults and contributing people today. They played in the drum and fife core. We’re on our way home but he was sitting there doing that. Never mind all his self-destructive stuff; it’s the good stuff we should focus on.

GT: Same thing with Charlie Parker.

WS: Yes.

Wayne Shorter YouTube Clips

The following clips give a taste of Shorter’s compositional and saxophone approach. But only a little taste, since his body of work is vast. He’s one of a handful of the most influential tenor saxophone stylists of the past 50 years. The most influential of the first several decades of jazz were Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young; Shorter is singular in a select group that includes John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, and, later, Michael Brecker.Shorter’s oftentimes elliptical compositions are stamped with genius. He joined Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers in 1959, and by the time of the first clip, recorded in 1963, he was the ensemble’s Musical Director. His compositions added another flavor to one of the most famous hard bop ensembles, which served as a finishing school for some of the biggest artists in jazz past to present, from Horace Silver, Lou Donaldson, Benny Golson, and Lee Morgan to Freddie Hubbard, Wynton Marsalis, Terence Blanchard, Donald Harrison, and Ralph Peterson Jr.

Here’s an original by Shorter, “Children of the Night,” and his featured solo. The other personnel are Art Blakey (drums), Cedar Walton (piano), Reggie Workman (bass), Curtis Fuller (trombone), and Freddie Hubbard (trumpet).

[line]

By the time Wayne Shorter joined the Miles Davis Quintet in 1964, Davis was a bona fide jazz star. Six years earlier he had recorded Kind of Blue, to this day the best-selling jazz album of all time. That ensemble (which, in addition to Davis, included John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Paul Chambers, Wynton Kelly, and Jimmy Cobb) comprised what became known as Davis’s First Great Quintet.

Shorter was the final piece of the puzzle for his Second Great Quintet. Miles once said about Shorter that “When he came into the band it started to grow a lot more and a whole lot faster, because Wayne is a real composer. He writes scores, writes the parts for everybody just as he wants them to sound. He also brought in a kind of curiosity about working with musical rules. If they didn’t work, then he broke them, but with musical sense; he understood that freedom in music was the ability to know the rules in order to bend them to your own satisfaction and taste."

Here’s Shorter’s “Footprints,” with one of the most renowned rhythm sections ever in jazz: pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Ron Carter, and drummer Tony Williams, who was just 19 years old at the time.

[line]

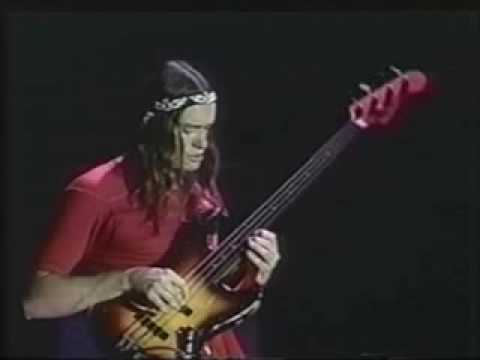

“Jazz Fusion” incorporated elements of jazz, rock and funk into a brew that defined a musical movement from the late 1960s through the 1970s, and presaged what became called “world music.” Weather Report was one of the, if not the best jazz fusion group of the time. Here are two songs, both by the keyboardist and composer Joe Zawinul, from their popular Heavy Weather (1977) album. The performances take place in Offenbach, Germany in 1978. The first, “Birdland,” was a hit, and was soon thereafter given further extension by the vocal group Manhattan Transfer with lyrics by vocalese master Jon Hendricks. The second, “A Remark That You Made,” has a gentle, yin feel. Peter Erskine holds down the drum chair. The electric bassist is Jaco Pastorious, an iconic bass god. Shorter’s soprano and tenor sax sound was the melodic glue.

In a good online piece on Shorter, “Eggs Scrambled Differently: A Look at Wayne Shorter,” Brad Jones recalls an instance in which before a Weather Report concert a young fan asks Shorter: what time is it? Time is relative, Shorter explained, and changes depending on where you are in the galaxy, and is eventually unknowable. Zawinul tells the young man: “You should know better than to ask Wayne a question like that. The time is 7:08.” Put that in your pipe and smoke it!

[line]

Fast forward to 2010 in Vienne, France with Shorter’s current quartet, comprised of Shorter and pianist Danilo Perez, bassist John Patitucci, and drummer Brian Blade. For my description of his current ensemble and words from Wayne about each band member, see the hyperlink to my New York Daily News feature at the beginning above. Oops, sorry Wayne: no beginnings! This Shorter original is aptly titled: “Adventures Aboard the Golden Mean.” It’s a song from his 2005 recording, “Beyond the Sound Barrier.”

Fast forward to 2010 in Vienne, France with Shorter’s current quartet, comprised of Shorter and pianist Danilo Perez, bassist John Patitucci, and drummer Brian Blade. For my description of his current ensemble and words from Wayne about each band member, see the hyperlink to my New York Daily News feature at the beginning above. Oops, sorry Wayne: no beginnings! This Shorter original is aptly titled: “Adventures Aboard the Golden Mean.” It’s a song from his 2005 recording, “Beyond the Sound Barrier.”

Here’s what Shorter once said about this original composition: “The golden mean is neither captive to the right, left, east, west, north, south or the middle. It’s attached to no extreme. That’s a place to try to get to in terms of freedom of thought and choice . . . And I think it has nothing to do with an almighty power or nothing like that, but a place that we have inside us that’s just asleep a little bit. And I’m thinking of it like a spaceship called the Golden Mean. I picture a lot of kids on there, flying around, having a good time. And they’re going somewhere along the Golden Mean.”

Members of the jazz community will say of Shorter that “He’s out there, man.” “He’s heavy, he’s deep” are other favorite sayings. Now Integral Life readers can add the expression “nondual” to the mix of descriptions of jazz master Wayne Shorter, as we strive to fly along the Golden Mean.