These videos are excerpted from the Fourth Turning of Buddhism collection, which includes a staggering 24 hours of high-definition video teachings by Ken Wilber and some of our most treasured Buddhist teachers: Diane Musho Hamilton, Doshin Michael Nelson Roshi, Patrick Sweeney, and Andrew Holecek.

The Fourth Turning program features in-depth explorations of the evolution of Buddhism — where it’s been, where it is, where it’s going—while offering a powerful and comprehensive guide for enlightened living in the 21st century.

Click here to save 40% or more off this collection! Expires on April 30th, 2023.

In addition to the three historic turnings attributed to Buddha, there have also been three evolutionary turnings that Buddhism has undergone (four according to some accounts, if you include Tantra. If so, we would be talking of a “Fifth Turning,” but we’ll keep it simple with the more common three so far.)

The first evolutionary turning, Theravadan Buddhism, is based on the realizations of Gautama Buddha himself, who illuminated the path of nirvana (the end of misery). The second turning, Mayahana Buddhism, stressed that “nirvana and samsara are not two.” The third turning, Vajrayana Buddhism, added an exquisite set of practices for realizing our true nature.

It has been over a thousand years since the last major evolution of Buddhism. Since that time we have witnessed astonishing advancements in science, art, psychology, technology, governance, values, cultural attitudes, and almost every other facet of our lives. These developments have utterly transformed our humanity, redefining our very sense of self in radical ways, and have brought a dramatic increase of freedom and material abundance to the world at large.

Buddhism, it would seem, may now be ripe for yet another turning of the wheel.

Watch as Ken Wilber introduces his Fourth Turning of Buddhism teaching, excerpted from his full 7-hour dharma talk.

Introduction to the Fourth Turning of Buddhism

by Ken WilberBuddhism has, of all the major religions, always had a very self-reflexive understanding of itself as growing, evolving, unfolding. Nowhere is this better seen than in Buddhism’s own notion of “Three (or Four) Turnings,” the idea that Buddhadharma itself (Buddhist Truth) has gone through three or four major turnings or evolutionary unfoldings, each adding to (but including) the previous turning.

The First Turning was represented by Gautama Buddha himself, the founder of the religion. It came to be expressed most centrally in the Four Noble Truths: 1) Life as we know it is suffering. 2) The cause of suffering is grasping. 3) To end grasping is to end suffering. 4) There is a way to end grasping, namely, the Eight-Fold Way (right view, right intention, right speech, right actions, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, right concentrative awareness).

Such was the essence of Buddhism for some 700 years, until the Buddhist genius‑sage Nagarjuna set forth his writings on Shunyata, typically translated as Emptiness (sometimes Nothingness, or the Plenum/Void). Nagarjuna (c. 200 CE) was increasingly skeptical of this strange dualism between samsara and nirvana (or, essentially equivalent, Form and Emptiness), that was central to Gautama’s teaching, believing rather that ultimate reality had no such dualisms but rather was, to put it somewhat metaphorically, a seamless nondual Whole (seamless, not featureless). The aim, thus, was not to get from one-half of this dualism (samsara) into the other half (nirvana), but to find the seamless Whole (Thatness, Suchness) underlying them. The cause of suffering is not knowing the Real, not knowing Emptiness or Reality in its Suchness, just as it is, free of limiting thoughts and concepts, and that which obscures the Real is drsta, or conceptualizing, qualifying, characterizing. Any concept makes sense only in terms of its opposite—infinite vs. finite, One vs. Many, Form vs. Emptiness, Up vs. Down, Spirit vs. Matter, etc.—and yet Reality has no opposite. In fact, according to Nagarjuna, you cannot say that Reality 1) is, nor 2) is not, 3) nor both, 4) nor neither, and that goes for any concept, any drsta, you can think of. Reality is not 1) infinite, nor 2) not infinite, 3) nor both, 4) nor neither. And so on through any concept, quality, characteristic, or notion you can think of.

Now the point of this fourfold negation—applied across the board—is not just a version of “neti, neti”—“not this, not that”—but to clear the mind from any dualistic thoughts or concepts (vikalpa or “dualistic thinking”) in order to make room for nondualistic awareness (or prajna)—the “jna” in English is “kno”—as in “knowledge”—or “gno”—as in “gnosis”—with “pra” being “pro”—thus, “prajna” is “pro-gnosis,” a nondual form of awareness in which the subject/object dichotomy is transcended—or the self/other dualism is seen through—leaving instead pure, undivided, nondual awareness—although, again, words such as “undivided” or “nondual” are metaphoric at best, since strictly speaking you can’t say this awareness, which is one with Reality, is 1) nondual, nor 2) not nondual, nor 3) both, nor 4) neither.) But the point, metaphorically, is that the dualism between Form and Emptiness, or samsara and nirvana, is mistaken, doesn’t really exist. As the Heart Sutra would summarize this view, “That which is Form is not other than Emptiness, that which is Emptiness is not other than Form,” which also means, “That which is samsara is not other than nirvana, and that which is nirvana is not other than samsara.” The point (again, metaphorically) is that dualities and concepts and qualifications tear the seamless Whole of Reality into torture-inducing, separate slices, and only by overcoming this fragmentation and alienation (via prajna) could a human find Wholeness, peace, freedom, release.

Such a profound notion was Shunyata that this whole approach was called the “Second Turning of the Wheel of Dharma (Truth),” and it marked virtually every subsequent Buddhist school henceforth. Among other things, by seeing that ordinary reality, just as it is, when seen in its Suchness, or Thusness, or Isness, is the same as the liberated state of nirvana, allowed a revolution in Buddhist practice. There is no ontological difference between samsara and nirvana, just an epistemological one—nirvana looked at through drsta is samsara, samsara looked at through nondual awareness is nirvana. Samsara and nirvana are “not-two” or “nondual” (and some schools, such as Zen, to emphasize the real “emptiness” or “nonceptuality” of the Real—and make sure “nondual” isn’t confused with “oneness”—would say they were “not-two, not-one” (which is why the “Wholeness” is metaphoric only; the point is that ultimate Reality can be realized or recognized, but not stated in words, all of which are dualistic and thus misleading).

But (within our metaphorical understanding), this was a profound revolution simply because now ordinary reality is the home of Enlightenment as well—our thoughts, desires, graspings, wishings are all “not-two” with ultimate Reality or Emptiness, and thus we can “bring everything to the path.” This would prove to be the opening to schools of liberation from Tantra to Vajrayana (“Diamond Vehicle,” e.g., Tibetan Buddhism). Such was the Second Turning. And in a crucial move, all of the basics of the First Turning were included—the Second Turning “transcended and included” the First Turning. Various subsequent schools of Buddhism would find ways to include the basic tenets of Gautama’s teachings with those of Nagarjuna’s, thus keeping Buddhism a seamless evolutionary stream. It was said, for example, that Gautama’s teaching on the emptiness of the self simply needed to be complemented with teachings on the emptiness of dharma (thing-events) as well—together, you had the full Emptiness view. So Gautama wasn’t so much denied as supplemented—again, giving Buddhism a very strong sense of evolutionary seamlessness and togetherness, even as new teachings were being introduced.

The very notion of the “not-twoness” of Emptiness and Form opened the door, as we briefly mentioned, to other even “stronger” versions of nonduality or (metaphoric!) Wholeness, one of the most prominent being the Yogachara, introduced by the half‑brothers Asanga (more of a brilliant innovator) and Vasubandhu (more of an acute synthesizer). Another name for their school—Vijnaptimatra—is usually translated as “Mind-only” or “Representation-only.” The point here is that the “not-twoness” of Emptiness and Form allowed some philosopher-sages to come up with other terms for the “Form” that was seamlessly conjoined with ultimate Emptiness or Shunyata, one of them being “Mind” itself. The idea was that “Mind” itself was the same as Emptiness—the Yogachara philosophers were adamant that they were talking about the same “unqualifiable” Emptiness that Nagarjuna was, but by also referring to it as “Mind” they were giving (some would say metaphorically, some would say absolutely) a type of compass that would help relate ultimate Emptiness to an everyday reality everybody was aware of (such as, namely, the Mind). The Zen saying, “The everyday mind, just that is the Tao (ultimate Truth)” is a good example of this type of Yogachara thinking. And it showed clearly how one could “bring everything to the path,” starting with your own, simple, everyday awareness. This opened so many other doors—especially Tantra and Vajrayana—that it is referred to as “The Third Turning of the Wheel of Dharma.”

Like many of the previous Buddhist schools, many schools of Buddhism after the Third Turning made explicit moves to integrate the teachings of the Third Turning with those of the previous two Turnings. There is even a school specifically called “the Yogachara‑Svatantrika‑Madhyamika” school of Buddhism that explicitly, as its name implies, attempted to integrate the teachings of Asanga and Vasubandhu with those of Nagarjuna (and, of course, Gauatama). Again, one constantly gets the sense of Buddhism understanding itself as a continually unfolding teaching, but one that “transcended and included” its predecessors, so it is an unbroken, evolving lineage of Buddhist teachings. I am really unaware of any other major religion that so self-consciously seems to have understood itself as a living, evolving, unfolding, but always “including” series of teachings.

(I mentioned that the Yogachara school opened up many other doors to “strong” nondual teachings, including Vajrayana Buddhism and Tantric Buddhism in general. Tantra particularly flourished at the great Nalanda University in India from the 8th to the 11th centuries CE. So profound were these developments that they have sometimes been referred to as a “Fourth Turning of the Wheel.” This is not as widespread an understanding as are the first three Turnings, but they were indeed profound nondual teachings. If we do count them as the Fourth Turning, then this simple introduction would be called “Toward a Fifth Turning,” and the existence of a Fourth Turning already in existence would simply make even stronger my claim that Buddhism has usually seen itself as a continually evolving and unfolding—“transcending and including”—teaching.)

My point can now be put simply. Even counting Vajrayana and Tantra as a Turning, and seeing their initial Nalanda growth phase as ending around the 11th century CE, that still means it has been close to a full millennium since Buddhism has recognized another major Turning. And yet, with items such as the Dalai Lama himself proclaiming that Buddhism needs to keep up with modern science or become obsolete, and—given Buddhism’s seemingly inherent openness to seeing itself as evolving and unfolding—and, finally, given all that we have discovered about the relative workings (if not absolute workings) of the mind in the West over the past millennium, it doesn’t seem grandiose at all to suggest that the time might indeed be ripe for yet another Turning of the Wheel of Dharma. Again, with reference to the Dalai Lama, he has worked so tirelessly on bringing leading Western authorities together with leading Buddhist teachers, looking for ways for both of them to enrich each other—and given the amount of material that Western researchers have unearthed on the mind’s relative workings—from stages of growth, to brain patterns during meditation, to states of consciousness and their functioning, to neurotransmitters and consciousness states, to various typologies of personality types and the different effects meditation has on each—there is a good deal of data and information that directly affects the central notions of Buddhism. Were this material discovered in, say, India during the 8th to 11th centuries CE, it’s hard to imagine that much of it wouldn’t be included in some of the schools of Buddhism. Buddhist thinkers have simply always been too smart, too sharp, too savvy to not include this type of material in their relentless drive to understand the mind and, in doing so, further understand ways to decrease human suffering.

What I will do in this very short introduction (“short” meaning, there is a longer version coming out as an eBook early next year, and soon after, an even larger book being brought out as a regular book, both by Shambhala Publications) is to give a list of three or four items that, in discussion with various Buddhist teachers, seem items that would be of most benefit to Buddhism in a new Turning. Please forgive the shortness of this introductory article; its very brevity makes leaving out much supporting evidence virtually mandatory, so I can only ask that you take an empathetic view here, and simply assume that there is indeed considerable evidence for the items I’m going to present, and then imagine what it would be like to have these as part of a general Buddhist teaching. Traleg Rinpoche and I had done exactly that in a book we were co-authoring tentatively called Integral Buddhism, but his shockingly abrupt passing-over brought that project to an end. It is with Traleg Rinpoche in mind (and, of course, all sentient beings) that I dedicate this work.

SOME EXAMPLES

1. Structures and States

Based on various types of research (which I’ll briefly explain in a moment), it appears that human beings have at least two very important—but very different—types of spiritual awareness. Forgive the technical terms here, but I think what is involved will become fairly clear. The first type is probably familiar to most: direct spiritual awareness, which involves what are technically called states of consciousness, and which are most often experienced in the practice of meditation or contemplation. For many meditative systems, there are between 3 and 5 major natural states of consciousness, and meditation is basically a systematic training to move through those states, starting at the lowest and densest and ending with the highest and subtlest (and ever-present, just not recognized). Both Vedanta and Vajrayana, for example, have versions of the following 5 states: 1) waking, 2) dreaming, 3) deep sleep, 4) empty or unqualifiable witnessing awareness, and 5) nondual “unity” awareness.

Each of those states of consciousness is said to be supported by a particular “body” (the states are said to be invisible and without simple location—where is “love” or “mutual understanding” located?—but the bodies are actual mass-energy forms running a spectrum from the grossest and densest to the subtlest and finest). These 5 bodies, supporting those 5 natural states of consciousness, are: 1) gross or physical body (Nirmanakaya in Buddhism—“kaya” means “body”), 2) subtle body (Sambhogakaya in Buddhism, 3) causal body (in Vedanta; “very subtle” body in Vajrayana, also called Dharmakaya or “Truth Body”), 4) Svabhavivakaya (in Buddhism, “Integrative Body”), and 5) Vajrakaya (in Buddhism, “Diamond Body”). Even when a system, such as Vedanta or Vajryana is aware of all 5 states and all 5 bodies, it is common for both of them to often just reduce these to 3 or 4, although always ready to draw on all 5 (Buddhism, for example, commonly reduces the bodies to the “trikaya”—the “three bodies”: Nirmanakaya [gross, form, or emanation body], Sambhogakaya [subtle, enjoyment, or transformation body], and Dharmakaya [very subtle or causal, Truth, or Emptiness Body]). Also, even though technically items like subtle body or causal body refer strictly to the body or mass-energy aspect, it is common to refer to the correlative state of consciousness with the same name—thus, gross consciousness, subtle consciousness, very subtle (or causal) consciousness, and so on.

Now the point about these states and bodies is that in most meditative systems, the meditative path itself starts at state 1 and progresses through the other states, in the order given, to state 5, or pure nondual Awakened Awareness. The point is that consciousness has passed through all states in full awareness, and thus achieves a type of “constant consciousness” that is itself the nondual union of Emptiness and Form—Emtpiness (or ultimate Dharma) not-two with all Form (gross form, subtle form, and very subtle form).

Thus, as for passing through the major natural states in that order (e.g., gross, subtle, very subtle, etc.), to give merely one example, Geshe Kelsang Gyatso gives the following 6 stages to Mahamudra meditation (Mahamudra, along with Dzogchen, are taken as some of the very highest of all Buddhist teachings):

- Identifying our own gross mind

- Realizing our gross mind directly

- Identifying our subtle mind

- Realizing our subtle mind directly

- Identifying our very subtle/nondual mind

- Realizing our very subtle/nondual mind directly

Thus, this general map of meditation stages comes from the natural states of consciousness all humans have (e.g., waking, dreaming, sleeping, ever-present nondual, etc.). This is probably why so many of world’s meditation systems are essentially so similar. Being biologically based (although not reducible to mere biology), they are the same for humans everywhere—in deep structure form, that is, while their surface features vary from culture to culture (and often within cultures). But, as only one example, Evelyn Underhill, in her classic text on Mysticism, claims all (Western) mystics go through the same basic stages of meditation: often following an initial awakening experience, the stages are: gross purification, subtle illumination, causal dark night (or infinite empty abyss, often followed by depression at losing the state before it becomes permanently realized), and nondual “unity” consciousness. The same basic gross, subtle, causal, nondual states are easily recognized. In fact, I did a book called Integral Psychology, which compared around 100 different developmental systems, about 1/3 of them being meditative systems and about 2/3 being similar to the type of spiritual awareness we will discuss next. What is so amazing about all of them—both types—is the essentially similar nature of them in each type, with similar stages easily recognizable in each (we’ll see this with the second type as well in a moment). In another book I co‑authored (with Jack Engler and Daniel P. Brown), called Transformations of Consciousness, we included a chapter by Harvard theologian John Chirban, who examined a dozen of the early desert Christian contemplatives and, yes indeed, the essentially same stages could be easily recognized (with those being similar to everything from St. Teresa’s Mansions to Zen’s Ox-Herding pictures).

So that is the first point I would like to make. Most schools of Buddhism (and most contemplative schools worldwide) have maps of meditation that are quite similar in deep structures. There are important variations, but there are also many, many important similarities, so much so that this deeply suggests some real and universal realities are involved here. The general stages of meditation, the types of awareness at each stage, and the general characteristics of each stage and the type of “knowledge” it delivers makes this entire area one to be taken with utmost seriousness. Meditation in general is delivering profoundly significant information about the human condition, the universe, and both relative and ultimate Truth.

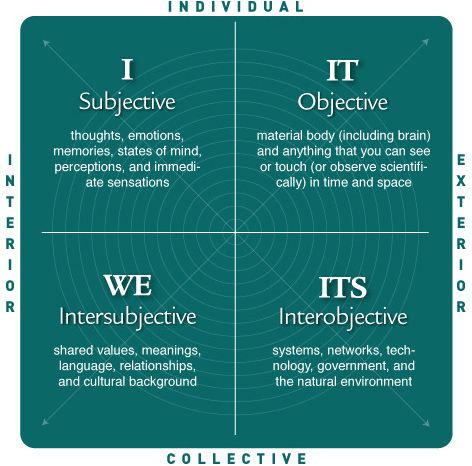

So that’s the first basic type of spiritual awareness humans seem to have access to—direct immediate experiences, based on states of consciousness, and generally called spiritual experience. The second type (and again, please forgive some of the technical terminology here, but I think it will come out clear) involves something called, not states, but structures of consciousness, and is often referred to as spiritual intelligence. Spiritual intelligence has many different definitions, but the idea generally is that, unlike spiritual experience, which is a 1st-person immediate experiential reality, spiritual intelligence is a 3rd-person, intellectual response to questions like, “What is it that is of ultimate concern to me?” “What is ultimate reality like?” “Who am I?” (1st-person perspective is the person who is speaking, and is generally taken to mean subjective or personal experience; 2nd-person means the person being spoken to—a “you” or “thou”; and 3rd-person means the person or thing being spoken about, and is taken to mean an objective fact or scientific truth.) Saying that spiritual experience is “1st-person” means it is a subjective, immediate personal experience in the awareness of the person—like almost any meditative experience (and “subjective” doesn’t mean unreal; it can mean important truths about the subjective realm, which meditation certainly seems to deliver). On the other hand, saying spiritual intelligence is “3rd-person” means it is not necessarily directly in the awareness of the person, but has been established to likely be present by careful scientific research and experiment, even if it is not in the direct awareness of the person. So most people have a 1st-person experience of speaking English when they do—it’s a direct experience for them; and they usually speak it correctly, using the rules of grammar correctly, even though they can’t write down what the grammar rules are—those rules are 3rd-person elements in their mind, not 1st-person elements, like speaking the language itself is.)

So, spiritual and meditative experiences are 1st-person, direct, immediate, subjective experiences. Spiritual intelligence is a series of structures in the mind that are not themselves directly experienced; they are 3rd-person structures that empirical research has determined people everywhere have—like rules of grammar—even though they are not directly aware of these structures. That’s a basic difference between states of consciousness and structures of consciousness—states can be immediately seen by looking within, structures cannot be seen by looking within but are deduced by scientific experiments on large groups of people over long periods of time.

So you can determine a state of consciousness by simply and directly asking the person what they are thinking or feeling. This is why maps of meditative stages have been around for at least 50,000 years, going back to the original shamans and their voyages to the upper and under worlds. But structures of consciousness are very recent discoveries in human history, being not much more than 100 years old. But they turn out to be very, very important…. (The recentness of structures’ discovery is also why states are found in all meditative systems, but structures are found in none of them—something a new Turning would surely take into account. More on that in a moment.)

Multiple Intelligences

One of the places we see structures of consciousness show up conspicuously is in what are generally called multiple intelligences. It used to be thought that a human being has only one or two basic types of intelligence—something like cognitive/logical intelligence and literary/humanistic intelligence—C.P. Snow’s famous “Two Cultures.” But starting with Howard Gardner, of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, the notion of “multiple intelligences” has now become quite widely accepted. The number of multiple intelligences, and exactly how to define them, is argued; but the fact that there are up to around a dozen multiple intelligences is uncontested—ones like cognitive intelligence, emotional intelligence, intrapersonal intelligence, moral intelligence, kinesthetic (somatic) intelligence, and spiritual intelligence. All of these are made of structures of consciousness, which means that although people will often use one or more of these intelligences, they can’t tell you the rules of the intelligence or its basic structure, just like they can’t tell you the rules of grammar, even though they are using it. They can’t introspect and see these structures of consciousness, the way they can introspect and see states. But they do have them. And one of them, it turns out, is spiritual intelligence. So this means a type of intelligence about spiritual issues, an intelligence you can’t see by looking within, but an intelligence that you definitely can use and engage to make spiritual decisions. And—just as important—we do have a fair amount of research on this intelligence and the answers that it gives. And that, as they say, is where the story starts to get interesting.

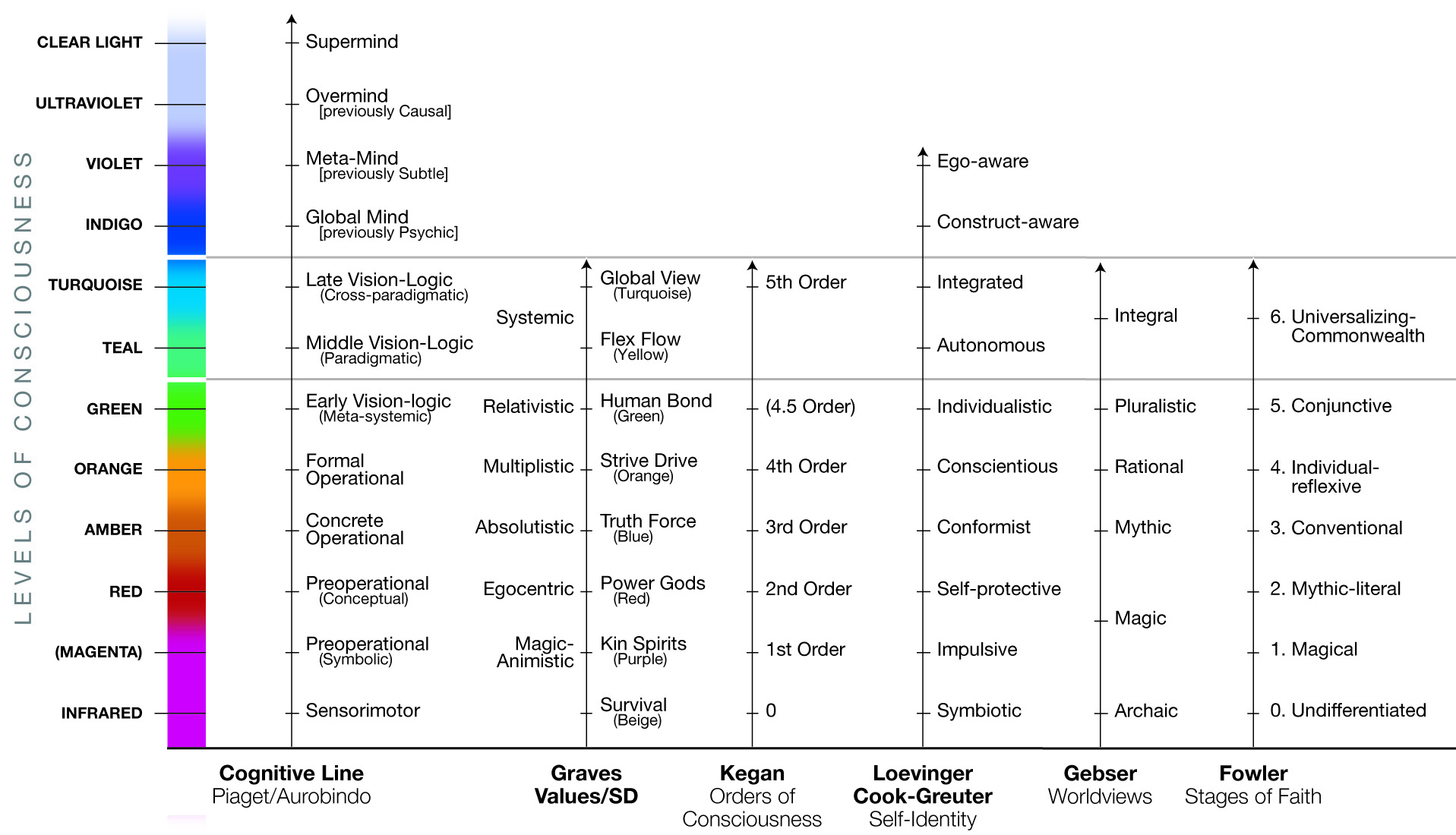

Now, as it turns out, virtually all of these multiple intelligences (which, because they show development, as all structures do, are also called developmental lines or lines of development), even though they are quite different from each other, all grow and develop through the same basic levels of development or developmental levels. So, different developmental lines, same developmental levels. This turns out to be important, because these lines develop at different speeds—they are relatively independent from each other. So you can be very highly developed in some lines (say, cognition and intrapersonal), mediumly developed in other lines (say, moral and emotional), and very poorly developed in yet others (say, somatic and spiritual). An example of somebody with very uneven development might be a Nazi doctor—high level in the cognitive line and very low level in the moral line. The overall average of the developmental levels of the various lines is called the structure center of gravity (just as it turns out that there is a states center of gravity, too, which we’ll get back to).

So, one of the things we have to be careful about is how we name these levels of development. Because all lines go through them, we don’t want to choose names that implicitly favor a few lines and ignore others. As it turns out, it’s actually quite hard to select level names that don’t do that—with up to a dozen developmental lines, almost any name will favor some lines more than others. So some researchers simply number the levels; others use colors. I do both, but it’s also helpful to at times have some names for the levels, even if they are slightly biased, because at least names give some information about the particular level, and don’t just leave people guessing what “#3 level” or “red level” looks like. So with that problem firmly in mind, I’m going to use a variation on the names that a pioneering developmentalist (Jean Gebser) used in exploring worldview lines. These level names—the names of the levels that all the multiple intelligence lines (including spiritual intelligence) grow and develop through—are: Archaic, Magic, Mythic, Rational, Pluralistic, Integral, and Super-Integral (with the occasional mixture, e.g., Magic-Mythic).

My next points can all be put very quickly, and I think you’ll start to get the picture: Each person has—in addition to the capacity to have direct spiritual experiences, as in meditation—a more intellectually-oriented spiritual awareness called spiritual intelligence. This intelligence, like the others, grows and develops through an Archaic level, a Magic level, a Mythic level, a Rational level, a Pluralistic level, an Integral level, and a Super-Integral level. And virtually nobody knows they have this intelligence—they cannot look within and see it, like they can meditative experiences. But this intelligence will govern all the major ideas a person has about spirituality and what it means. Structures, it turns out, are how we interpret states (and all other experiences, for that matter).

So you could be a meditator, and you could be at, say, the causal stage. If your center of gravity is at the structure level of Pluralistic, then you will interpret the experiences of this causal stage in a Pluralistic fashion (we’ll explain more what that means in a moment). If you’re at a Mythic level, you’ll interpret the same causal stage in a Mythic fashion. If you’re Integral, you’ll interpret—and experience—the causal stage in an Integral fashion. And yet none of this will be conscious to you, any more than when you use English, you’ll be aware of the rules of grammar you’re using. So of these two types of spiritual awareness, one of them is virtually completely unaware to you, no matter how advanced you are in states or in meditation. It simply won’t cross your mind, although its results will. The other type—such as meditative experience or states—will be available to your awareness directly, and as you meditate, the whole point is the conscious experiences and understandings of you and your world that you will get at each of the major stages of meditation (e.g., gross, subtle, very subtle, mirror mind, nondual). And, it turns out, this meditative understanding will be directly related to, and molded by, the structure level of development that you are generally at (e.g., Archaic, Magic, Mythic, Rational, Pluralistic, Integral, Super-Integral).